The Meaning of Capitalist Elections / 2024 Wrap-Up

Learning from Alain Badiou's 2008 response to the French Presidential electoral victory of Nicolas Sarkozy + A simple end of year PSA RE: Baklava Bolshevik.

2024, for all its political evils and personal disruptions, was a year in which I finally set out to “do writing”, not as a career (come what may) but as an essential mode of thinking and expression. A certain number of years after concluding university study became one too many without a regular writing schedule facilitating sustained engagement with the art I love and hate, politics and philosophical texts and ideas. Out of this breach, Baklava Bolshevik emerged, and since getting up and running, more than 130 interesting people from around the world have joined me here. I want to send each of you my warmest thanks—when one randomly self-publishes a 3000-word philosophical essay about the Barbie movie, they never expect such a gracious response, much less active encouragement.

Between full-time employment and extensive travel in Turkey, I had the great fortune to be asked to write two book reviews for Meanjin and an essay about one of the year’s best films, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, for Arena. I also started a Twitter account to mingle with other writers and get the word out (we do a little posting as a treat). Speaking for myself, writing is a process that requires prolonged preparatory thought and the ordering of ideas to a particular degree of confidence before penning even an initial word, much less a paragraph. I am determined, though, to find as much such space and time as possible—it’s just something I need to do. I want to improve. Any opportunity to work with an editor is therefore precious, and something I’d like to do more of. Much of the time, however, it simply isn’t possible. During such moments, I try to stay on the horse. Sometimes, it leads to something cool, like my essay on Japanese director Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist, which remains the cinematic jewel of 2024.

I also wrote a lot of monthly newsletters—Reading, Watching, Listening—which enabled me to experiment with reviewing a book, a film (or, as often happened, two films) and an album each month. This was an excellent exercise for building nimbleness and provided steady practice. Still, life will always get in the way, and I feel they become rather jam-packed in a way that dilutes the importance of any single point of focus. I may still dabble in writing these occasionally, but I want them to be less regular in 2025. Instead, I’ll invest the energy and newfound space to round out pieces that could otherwise stand independently but were stuffed into thick, slightly gauche sets of “recommendations”. As a structural matter, releasing three pieces-within-a-piece via Substack every month tends to bury an individual topic of note in a “post” that seems out of date the very next month, despite being just as effortful as standalone writing.

As a proof of concept, and as I’ve had so many new people join me, I’m plucking one such piece out and republishing it here for those who missed it. 2024 was a year of deepening political crisis and right-wing reaction globally, and this review of Alain Badiou’s 2008 book, The Meaning of Sarkozy, is a helpful philosophical outline of how to think about elections in modern capitalist ‘democracies’, where they generate a tremendous amount of negativity and disorientation. We saw this nowhere more than the return of Donald Trump to the White House in the world’s imperial superpower, the United States. The ideas discussed in this review were further developed in a broader essay that came on the heels of Trump’s entirely predictable resurgence, in which I linked the logic of late capitalist terrorism, screen society and elections—and called for a new paradigm of thinking about and engaging with these hegemonic phenomena. I hope this serves as a welcome to newcomers and clarifies my direction for those who have been with me a little longer.

I may continue to steadily pluck and republish similar previously newslettered pieces while I work on bringing you some fresh writing. Until then, thank you again for your attention and support—I wish you all the best for 2025. Look after yourselves and each other.

Confusion, fear, and anger—these three emotions dominate individual and collective human experience today. Life is now overwhelmingly mediated by social media monopolies, which are themselves engineered to produce confusion, fear, and anger because, well, they can be highly profitable. The headline consequence of this mass affective disorder is the creeping loss of legitimacy suffered by the institutions of liberal democratic capitalism: trust is plummeting in corporate media and government with few exceptions.

This is why you hear liberal authoritarian decline managers across the ‘West’, such as Australia’s ex-Minister for Home Affairs and Labor Party member Clare O’Neil, constantly bemoaning the rise of “populism”. Yes, the Minister who until only recently presided over the country’s categorically illegal and torturous regime of racial persecution against asylum seekers is whining that her symbiotes in the domestic far-right take advantage of such signals to stoke further anti-immigrant xenophobia. She drops a line to The Guardian telling us how important it is not to listen to racialising Rightist agitators from on high, all the while unreasonably denying visas to Palestinians attempting to flee the genocide in Gaza.

And yet, while profuse, embittered dissatisfaction and disaffection now pervade Western democracies, it is just as clear that, in the absence of any genuine anti-systemic alternative, meaning a radically left-wing force, the system is consistently renewed at the ballot box at the end of each term of government. In simple terms, the vast majority of people continue to ritualistically affirm the exact state of affairs through which their confusion, fear and anger arise and which, in the main, rules at their expense.

As the progress of human civilisation remains deferred in this purgatory of constant oscillation at arbitrary intervals between ‘democratic’ and ‘conservative’ ideologies of capitalist governance, it is apparent that protraction will come at unthinkable costs. The first industrial-scale genocide of late modernity grinds on in Palestine at the behest of the so-called liberal democratic West. More than 300 days of the campaign of extermination has not been enough to satiate the bloodthirsty bureaucrats of Israel’s Western patron states, who remain “committed” to arming the exterminators of the Palestinians. Those opposing this epochal crime have been subjected to predictable smears, censorship and criminalisation by the very cowards crying wolf about the anti-democratic strain of their electoral opponents.

At the same time, that older, more base form of racial violence, the pogrom, is once again finding purchase in the lexicon of hate everywhere from the United Kingdom to India and Türkiye. This crisis is general to the bourgeois national form itself. It would be naive to focus here only on the rise of what I term electoral fascisms in the West alone—while Western media obsesses over MAGA and the emerging far-right bloc in Europe, many other societies can model more advanced forms of the coming barbarism. What it says that ‘late fascisms’ can thrive inside the liberal democratic configuration of capitalism itself, without strictly needing to resort to the extraparliamentary tactics of historical fascism, will have to be left to future discussion.

This brings me to my favourite book, which I have read since the last newsletter, The Meaning of Sarkozy. Once again, its author is the radical French philosopher Alain Badiou, whom I also reviewed in a previous edition. I must confess to benefitting a great deal from Badiou’s writing, which is exceptionally clear in its philosophical logic and equally vigorous in its political, aesthetic, and ethical convictions. I consulted this book, first published in English in 2008, in the wake of this year’s snap-election in France, which delivered a curious temporary setback for the local electoral fascist formation, Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National. My interest was in cross-referencing my analysis of contemporary events with Badiou’s tracing of a particular longstanding reactionary tradition within France, hoping that doing so would help me better understand the crisis within liberal capitalist governance more generally. As is often the case when reading Badiou, I emerge with a stronger understanding of the complexities at hand and invigorated with the defiance required to avoid resignation to the crisis.

The book is relatively short, frontloaded with an analysis of then-President of France Nicolas Sarkozy’s particular meaning as a symbol of the broader “restoration in the restoration”, the return of a mass conservative subjectivity once threatened by powerful left-wing movements. Fear is critical to this form of thought and expresses itself through bourgeois elections as “the contradictory entanglement” of two types of fear. Badiou calls the first of these the essential fear: this is the inciting fear experienced by the privileged classes—the fear of losing their status as dominants, which they correctly see as insecure but wrongly ascribe this threat onto, for instance, migrants and the poor, rather than the tiny oligarchy above them and the capitalist system they enforce (private property, commodity exchange, etcetera). The second fear is a derivative fear held by those uncomfortable with the authoritarian policies proposed by the first group. But in lacking a clear political vision, manifesting solely as anxiety and not action, this derivative fear folds itself into the essential fear more often than not.

Badiou identifies fear as central to the democratic process in contemporary liberal capitalism, a process that quite intentionally allows elections to function apolitically. If politics is organised collective action according to certain principles and aiming to bring about a new reality repressed by the status quo, then when we vote in bourgeois elections today, we are not doing politics at all. For Badiou, “a subjective index of this omnipresent affective negativity” defines the capitalist electoral subject where the major parties underwrite each other’s commitment to the system. In this context of false choice, voting carries no political conviction beyond which form of fear—fear, or the fear of fear—one most feels. In this fashion, capitalist elections are “organised disorientation”, presenting a fallacious choice between mere affects and not at all distinct political paradigms. Through this process, the state is validated purely through fear, getting armed with a mandate to “become terroristic” at the level of oppression and carceral controls, augmented by contemporary technology.

With it established that impotence is the rule within electoral democracy, Badiou continues rather amusingly to excoriate the particular French expression of the ritualistic worship of “democracy”, where voting is not strictly compulsory. He notes that politicians and commentators unanimously praised the high turnout in the 2007 election as a success of democracy, despite the vote delivering a feverishly reactionary President in Sarkozy. Again, Badiou points to the lack of political substance in such celebrations: “This means that democracy is strictly indifferent to any content – that it represents nothing more than its own form”. We are told to rejoice in the abstract that people came out to vote. “Certainly,” Badiou continues, “this only organised a disaster, of which we shall suffer the calamitous consequences, but all glory to them! By their stupid number, they brought the triumph of democracy”. In no other field, Badiou reminds us, do we consider something prima facie valid independent from its actual effects.

There is more to Badiou’s criticism of ‘capitalo-parliamentary’ democracy here, from elections being an instrument of repression as opposed to that of expression, which they claim to be, to their consistent, widespread depressive psychological impacts. To counter these deleterious effects and renew an authentic form of mass participatory politics, Badiou proposes eight initial theses, which he encourages us to experiment with and add to, in keeping with his commitment to fostering a philosophy for militants. Significantly, these proposals range from the concretely political to reasserting the supremacy of scientific knowledge to its appearance in for-profit technologies and of art as creation over simple consumption.

Point 4, “Love must be reinvented”, is Badiou at his bleeding best, making a robust case that against contemporary conceptions of love on left and right, we should affirm that love begins “beyond desire and demand”, though it embraces both. For Badiou, love is “an examination of the world from the point of Two”, meaning it can never be reduced to an individual’s territory. As such, love is always “violent, irresponsible and creative”. To rescue love from “the mutilation that the supposed sovereignty of the individual imposes on human experience”, we must learn from love itself that the individual, as such, is “something vacuous and insignificant”.

In considering the surging electoral fascisms of late capitalism, Badiou devotes an entire chapter to Point 8, that “There is only one world”. Here, Badiou critiques contemporary capitalism for engendering a society starkly divided by wealth, where there is not a singular world of human beings but rather a fragmented existence marked by barriers, from Israel’s apartheid wall to the ruthless border-torture regimes of the USA, UK and Australia. This arbitrary division fosters exclusion, destroying the notion of a unified global humanity and laying the basis for nativist animus, now increasingly spiralling into pogromism.

Badiou intends that “there is only one world” not merely be a declarative statement but a performative act—a political imperative demanding the recognition of the inherent equality and coexistence of all human beings, irrespective of their cultural or national differences. He poignantly asserts that this unified world should transcend the superficial “unity of objects and monetary signs” propagated by global capitalism (the “false single world”), which necessarily produces partition and violence. Instead, Badiou envisions a society that celebrates diversity, asserting that true unity emanates from acknowledging and constructively engaging with these differences.

Central to Badiou’s argument is the critique of “integration” imposed by Western democracies, which he views correctly as a form of cultural erasure. He fervently advocates for the right of individuals drawn from different societies to maintain and develop their unique identities while actively participating in the single world, wherever they may find themselves at a given point in time. Badiou’s vision is doggedly inclusive, advocating for a politics of universal equality and shared existence without raising identity to the highest principle of political thought or action. Such an approach is a precondition to toppling the barriers erected by capitalist globalisation, which serve to segregate and marginalise rather than conjoin. Badiou’s exploration of the “one world” is also notable for its metaphysical qualities, especially his notion that the world is transcendentally the same because the beings within it are different. This dialectic, where unity arises precisely from difference, points the way toward extinguishing the capitalist divisions that stoke vile persecution today.

Rounding out his alternative to the crisis of capitalo-parliamentarism, Badiou reiterates the necessity of the Communist hypothesis as a guiding principle in the struggle for human liberation. Vitally, Badiou begins by situating Sarkozy as the symbol of a period of complete dominance of capitalism and bourgeois ideology, which continues today. However, while the system currently enjoys unchallenged dominance, the mere fact of this historical interval where the Communist Idea is in retreat does not diminish its essential correctness. Badiou understands that abandoning this hypothesis—the Idea of a different world being possible, one where the class structure and state apparatus are abolished, and humanity achieves basic unity and freedom—would mean resigning ourselves to the vicious logic of the market and parliamentary cretinism.

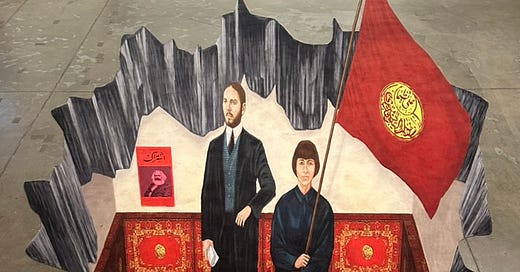

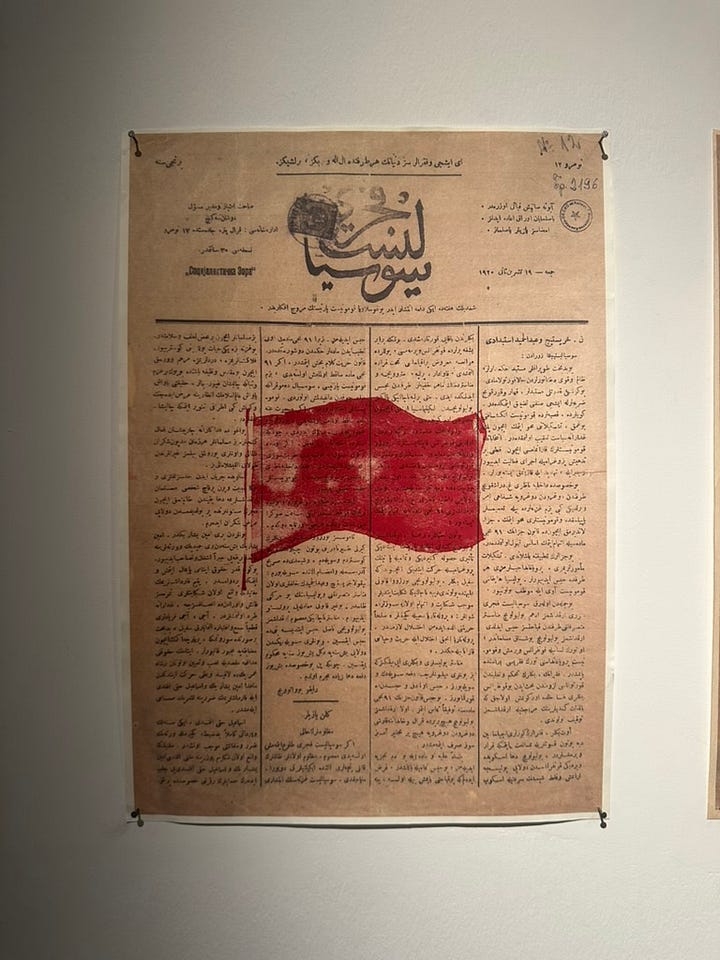

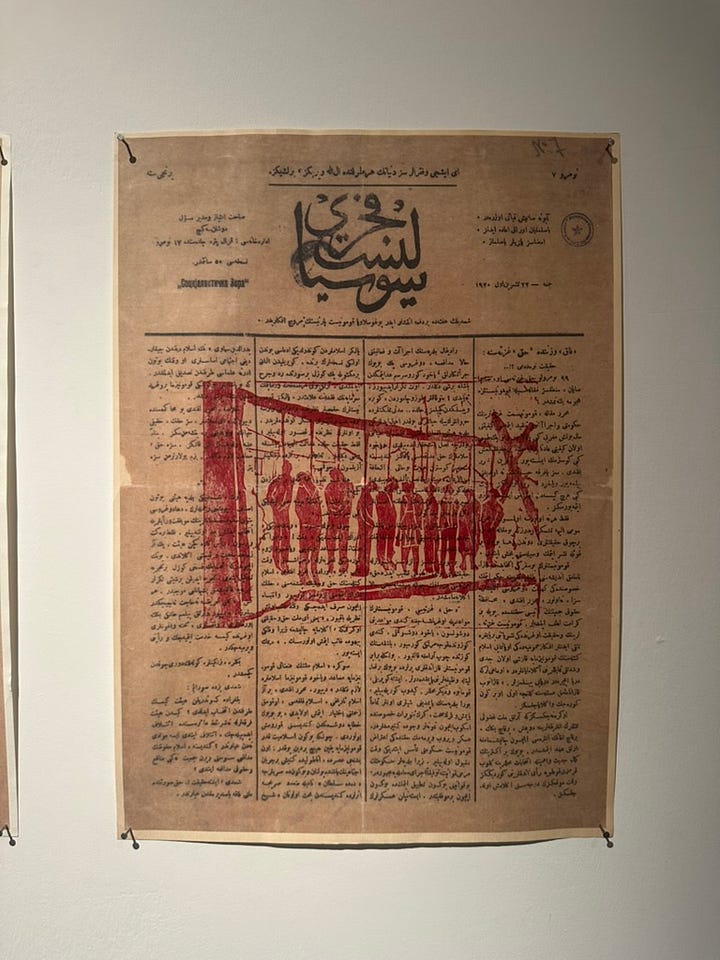

!['History Otherwise: Ottoman Socialist Hilmi and Ottoman Women's Rights Defender Nuriye' depicts representatives of two significant movements from the late Ottoman era in an Ottoman-style living room, situated under the ground as if within an archaeological excavation site. Inside the room are Hüseyin Hilmi Bey (1885-1922) and Nuriye Ulviye Mevlan Civelek (1893-1964). Nuriye Ulviye Hanim was the founder of the Ottoman Society for the Defense of Women's Rights (1913) and the owner of its publication, Kadinlar Dünyasi [Women's World] (1913-1921). Kadinlar Dünyas/, whose staff consisted solely of women, was the only radical feminist publication of the time, focusing on women's participation and rights in politics, education, and the workforce. Hüseyin Hilmi Bey, also known as istirakçi Hilmi, was one of the early socialists with liberal views and a founding member of the Ottoman Socialist Party in 1910 and the Socialist Party of Turkey in 1919. In 1910, together with Baha Tevfik, he launched /stirak [Participation/Communism/ Socialism], the official publication of the Ottoman Socialist Party, which ran for twenty issues. The magazine covered topics such as the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms, the problems of peasants, and news from around the world.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_720,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb5a8bda5-2047-44cd-98af-f97036383d77_768x1024.jpeg)

!['History Otherwise: Ottoman Socialist Hilmi and Ottoman Women's Rights Defender Nuriye' depicts representatives of two significant movements from the late Ottoman era in an Ottoman-style living room, situated under the ground as if within an archaeological excavation site. Inside the room are Hüseyin Hilmi Bey (1885-1922) and Nuriye Ulviye Mevlan Civelek (1893-1964). Nuriye Ulviye Hanim was the founder of the Ottoman Society for the Defense of Women's Rights (1913) and the owner of its publication, Kadinlar Dünyasi [Women's World] (1913-1921). Kadinlar Dünyas/, whose staff consisted solely of women, was the only radical feminist publication of the time, focusing on women's participation and rights in politics, education, and the workforce. Hüseyin Hilmi Bey, also known as istirakçi Hilmi, was one of the early socialists with liberal views and a founding member of the Ottoman Socialist Party in 1910 and the Socialist Party of Turkey in 1919. In 1910, together with Baha Tevfik, he launched /stirak [Participation/Communism/ Socialism], the official publication of the Ottoman Socialist Party, which ran for twenty issues. The magazine covered topics such as the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms, the problems of peasants, and news from around the world.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_720,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6eaa2ea1-42da-4ed1-8c15-f7ee1eeae787_3024x4032.heic)

In making the case for Communism’s enduring relevance, Badiou critiques the reduction of the Idea to the wayward experiments of the 20th century while cautioning radicals against attempting to organise a return to these failures. Badiou’s vision is one where the human species can finally realise its potential through collective organisation rather than being trapped in the cycles of exploitation that have defined history since antiquity. In short, Badiou urges us to reclaim Communism as a dynamic Idea (and not a rigid political structure) that must continue to guide efforts towards true human emancipation.

It is one of the many tremendous virtues of Badiou’s writing that he can condense all these philosophical arguments and many more I haven’t explored in just over 100 pages. This kind of cutting, urgent intervention stands in stark contrast to the ceaseless and fatuous babble of liberal commentators and ideologues, who gleefully participate in the engineering of a world that Badiou rightfully views as beneath humanity. There is also something to be said for returning to The Meaning of Sarkozy now, after almost two decades of further decline and crisis within Western liberal democratic capitalism. The analysis and arguments laid down by Badiou some 17 years ago have only found greater salience as the terrible policies of racial, sexual and other oppression of capitalist states have given rise to a growing body of anxious, angry and violent thugs willing to take the dominant “order” into their own hands. To defeat the protofascist mob, as Badiou says, we must throw off the illusion of parliamentary elections and assert that there is only one world while devotedly constructing it.