Reading, Watching, Listening / 31.05.2024

Communism, Brian De Palma and Mach-Hommy make for an interesting month.

Another month, another modest list of the best things I have been reading, watching and listening to recently for your enjoyment. I apologise that I haven’t had anything to publish here recently—I’ve had a difficult month with my health and personal circumstances. Fortunately, this is coming to a close, and I will have ample energy to expend writing, which I greatly anticipate.

Speaking of which, earlier this year, I wrote an extensive essay on the cinematic and political significance of the Barbie and Poor Things 1-2 punch, which I submitted to several publications. The impetus for writing it was my frustration with the vain, self-congratulatory dismissal of Barbie on the radical left. The essay is heavily philosophical and involves more discussion of the plot (for analytic purposes) than publications typically go for.

In light of this, I’ll give it another pass in the coming days and self-publish it in Baklava Bolshevik. My hope is that you will approach with an open mind and perhaps come around to a closer and more philosophical reading of Barbie, especially. I look forward to your feedback and reflections—don’t be shy!

Without further ado, here is the third edition of Reading, Watching, Listening.

Reading: ‘The Communist Hypothesis’, Alain Badiou

This month’s reading rec is admittedly sectional: it blends philosophical and political discourse that requires readers to have a certain level of understanding of communist politics and history. Unfortunately, recent personal challenges have meant that I couldn’t do as much reading as I would’ve liked. This book is quite simply the only one I managed to finish. Nevertheless, I believe it is paramount for as many people as possible to begin investigating and familiarising themselves with communism and its history. It would be best if you weren’t deterred—now is always the best time to start learning.

For those unfamiliar, our author, Alain Badiou, is a highly regarded figure within contemporary philosophy. But unlike most in academia, he has doggedly refused to abandon genuinely revolutionary political thought following the defeats suffered by the radical movements of the 60s and 70s. Born in 1937 in Rabat, Morocco, and later raised in France, Badiou’s intellectual journey has always been deeply intertwined with his political activism. A diligent student of Louis Althusser, an antagonistic contemporary to Gilles Deleuze and a participant in the events of May 1968, Badiou’s work is a fusion of rigorous philosophy and revolutionary zeal. The Communist Hypothesis exemplifies this blend, offering a powerful critique of defeatism and a compelling case for the enduring value of ‘the communist Idea’.

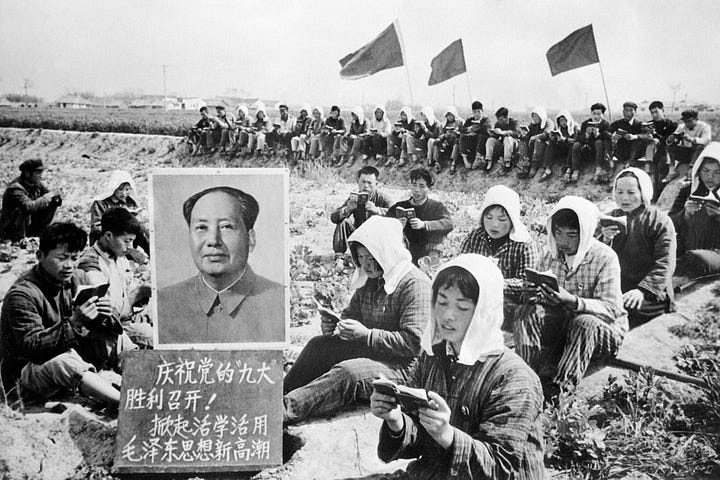

The beating heart of The Communist Hypothesis, structured as a collection of essays, is a vehement rejection of the notion that communism is a defeated or obsolete project. Badiou argues that declaring the end of communism is either an empty triumphalism if proclaimed by its adversaries or a deep pessimism if accepted by its former advocates. This is not to say that Badiou ignores or handwaves the fact that all experiments named for ‘socialism’—from the Paris Commune to the Stalinised USSR—ended in ‘failure’. Badiou is among the communists who engage in the essential critique of these episodes; the first essay in this collection problematises and categorises such failures. Critically, however, these autopsies are driven by Badiou’s project to salvage the fundamental and necessary truth contained in the Idea of communism as an objective of political struggle.

Badiou is correct that it is imperative to resist the bourgeois narrative that the collapse of the Soviet Union marks the end of communist potential. What follows is that we must reexamine, reimagine and reanimate the communist hypothesis, as it remains a vital framework for creating a future of genuine universality and equality. It is delightful to follow Badiou’s reasoning that we must return to the basic prospect of communism: a world where the well-being of one is intrinsically linked to the well-being of all. This egalitarian principle, he argues, is more relevant than ever in an era marked by sustained systemic crisis and widening inequality. For Badiou, preserving this Idea is not merely an intellectual exercise but a moral imperative. This is because the notion of a genuinely equal world provides a beacon of hope and a guide for political action.

Badiou outlines two significant sequences in the history of the communist hypothesis. The first sequence spans from the French Revolution to the Paris Commune, marking the birth and early development of communist theory. This period is characterised by the emergence of a radical vision of society grounded in the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The second sequence extends from the Bolshevik Revolution to the end of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, encompassing the rise and fall of 20th-century communism. These historical sequences illustrate the evolution of the communist hypothesis and explore the recurring challenges revolutionary movements face. It is a pleasure to receive a sweeping analysis from a veteran radical.

One of Badiou’s most provocative arguments is his rejection of returning to the models of the 19th-century mass movement or the 20th-century communist party. The need to learn from past failures is essential wisdom. Still, I appreciate Badiou’s unwillingness to make the mistake of some socialists, who virtually wholly sever themselves from these historical experiences. In contrast, Badiou argues we must remain faithful to the lessons of significant revolutionary Events, particularly his pet favourites, May 68 and the Cultural Revolution. We are at the very beginning of a new phase in the development of the communist hypothesis, one which, according to Badiou, renders traditional models incapable of addressing the complexities of contemporary political struggle. Instead, Badiou advocates for new forms of political experience that can better realise the communist Idea. He calls for innovative organisational structures and strategies that transcend the hierarchical and bureaucratic tendencies of historical communist parties.

I agree with Badiou that a forward-looking but historically informed approach is crucial for revitalising communism and making it relevant to present challenges. Badiou leaves what forms and strategies may offer promiseful experimentation to revolutionaries largely vague. While understandable—no one person could ever prescribe the exact correct courses of action—this lack of formulation is a trend with even the most critical communist writers. This is painful because it is precisely what is currently needed: experimental propositions for revolutionary political organisation and activity that can be implemented and battle-tested. Isabelle Garo’s vast and eclectic Communism and Strategy, which contains a critique of Badiou among other thinkers, starts this vital collective task.

Watching: A Double Dose of De Palma – ‘Body Double’ (1984) and ‘Blow Out’ (1981)

Last night, I had the pleasure of experiencing a Brian De Palma double feature at Melbourne’s Astor Theatre, showcasing Body Double and Blow Out. These films—brimming with De Palma’s signature style and thematic preoccupations—offer wildly entertaining explorations of prescient concerns that are strikingly relevant today. During the 80s, De Palma was evidently fascinated with the elusiveness of truth, the perils of male impotence and sexual obsession, and the corruption and unresponsiveness of official institutions. From our historical vantage point, one can only conclude that the man was onto something.

Body Double screened first. As the reel started spinning, my friend and De Palma aficionado Hamish warned me I was in for something extraordinary. The plot centres around Jake Scully (Craig Wasson), a struggling actor embroiled in a murder mystery after spying on his beautiful neighbour, Gloria Revelle (Deborah Shelton). In this way, Body Double is a vigorously campified update to Hitchcock’s Rear Window and Vertigo, bringing them into an age where cinematic voyeurism and fantasy have become so powerful as to supplant reality. De Palma’s exploration of male leering here is not a mere plot device or pastiche. Instead, it forms a configuration of Hollywood filmmaking into the precise shape of the slobbery masculinity it often serves.

I don’t believe I’ve seen a more pitiable protagonist than Jake Scully, painfully conjured by the boyish Wasson. The character’s apparent ‘soft’ masculinity, true to life, belies something significantly more perverse. Jake’s physical and psychological immotility channels a pusillanimous current within male subjectivity that has increased in deviance since the film’s release. His sheer obsessive fetishism is the very source of his inability to act decisively upon the world, representing the collapse of the ‘performance’ of masculinity under the weight of its plasticity. He likes to watch—so he may only watch.

The double feature closed with Blow Out, which follows Jack Terry (John Travolta), a movie sound tech who inadvertently records a car accident that is a political assassination of the likely incoming President. This film is more intensively concerned with the complexities of uncovering the truth amidst a web of deception and conspiracy, something Body Double approaches rather cartoonishly. De Palma’s focus on the auditory elements—creepily crafted sounds and eerie silences—serves as a metaphor for the struggle to make sense of contradictions within reality (something that is once again beginning to prominently concern filmmakers).

Jack is consumed by a need to piece together sounds and images, cross-referenced with his memories, to reveal the truth. This quest runs up against both institutional indifference and concerted cover-ups. As liberal democracies continue pioneering authoritarian state censorship, too often claiming the freedom of the few driven by their conscience to become whistleblowers, Jack’s total inability to make objective reality count for something feels prophetic. The film’s genuinely bleak and meanspirited conclusion is among the more audacious narrative choices in a career littered with them.

Both Body Double and Blow Out feature ‘strangler’ killers, who target women with the pervasive violence that is often sensationalised—yet inadequately addressed—by the culture industry and society more broadly. Despite their best efforts, the male protagonists are pathetic failures, unable to save the victims or themselves. Their feebleness and monomania are necessary for De Palma’s female characters to become mortally endangered.

De Palma’s films are also profoundly reflexive, providing an unflinching critique of Hollywood and independent cinema. Body Double’s Hollywood setting allows De Palma to satirise the industry’s exploitation of sex and violence. At the same time, Blow Out examines the manipulative power of film and media in shaping perceptions of reality. Both films underscore how traumatic memories shape people’s present behaviours—the sole reservoir of sympathy De Palma lends to his leading men. All this amounts to enthralling, splenetic cinema, allowing no respite from the litany of social ills that dominate us.

If you haven’t already, submit yourself to these stupefyingly stylish apogees of De Palma’s vision—a vision that has only grown in salience since the 1980s.

Listening: ‘#RICHAXXHAITIAN’, Mach-Hommy

Let’s face it: I was never going to recommend anything other than Mach-Hommy’s latest album, #RICHAXXHAITIAN, this month. The music press is prone to label the American rapper of Haitian descent as elusive or reclusive. Perhaps superficially, this is true—similar to his contemporary and occasional collaborator billy woods, Mach maintains a degree of anonymity. He puts deliberate distance between himself and the media and mainstream. Most famously, he wields the full force of copyright law to forbid the publication of his lyrics online.

What this label misses, however, is that since 2011, Mach has been among hip-hop’s most prolific artists, whose dedication and pride in the craft of rapping is, alongside his Haitian identity, the guiding force of his music. In many ways, Mach’s ‘reclusiveness’ is not a retreat but a resolution, a self-affirmation of the purity and integrity of his creative approach. #RICHAXXHAITIAN is a testament to the premium Mach places on his artistry, showcasing an extraordinary range of flows, diverse production styles, and thematic depth that set him apart from the generic hip-hop of the moment.

The album’s brilliance lies in Mach’s uniquely deft suite of flows, deployed across a grand musical mosaic. #RICHAXXHAITIAN features an impressive array of sounds brought to life by a strong roster of underground producers, including Conductor Williams, Quelle Chris, and Sadhugold. Each track is meticulously crafted, often containing several distinct segments that traverse various genres without diluting Mach’s cohesive sonic signature. Notably, Mach’s father was a folk guitarist, and he credits him as influencing his musical style. Nowhere is this more palpable than on this newest album.

“Sonje” and “The Serpent and the Rainbow” encapsulate Mach-Hommy’s folkish storytelling, vocal versatility and innovative sound. On “Sonje,” his flow is fluid and linguistically complex, repeatedly shifting rhythms and even languages over the jazz-inflected beat and the soulful melodies of Georgia Anne Muldrow. The track’s title, meaning “remember” in Haitian Kreyòl (a language Mach frequently raps in), sets the tone for an album deeply rooted in memory and cultural knowledge. In contrast, “The Serpent and the Rainbow” blends elements of Caribbean rhythms with haunting and atmospheric production resembling the score of a silent horror film. The song’s bridge sees Mach dip into whimsical, sweet singing—it would be challenging to claim another rapper working today is more effortlessly dexterous.

This artistic sophistication contrasts starkly with prevailing trends in mainstream hip-hop, characterised by a lack of the lyrical and rhythmic complexity that Mach-Hommy delivers with ease. While much of today’s hip-hop is decidedly repetitive, #RICHAXXHAITIAN is a masterclass in lyrical depth and rhythmic innovation. Every track has its own narrative rich with allusion and metaphor, demanding attentive listening that offers fresh insights with each play.

Central to #RICHAXXHAITIAN are Haitian pride and culture, familiar ground for Mach but rendered here with breathtaking fidelity and political urgency. Mach imbues this record with a deep sense of heritage, celebrating the resilience and resistance that characterise the Haitian spirit without shying away from Haiti’s present or historical political and economic struggles.

Take, for instance, “POLITickle”, a meditation on neocolonial oppression that highlights explicitly the detrimental role of the institutions of global capital. Namely, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is “a monkey” on his back, “and it’s a rather heavy one”. Those who wish to learn precisely how international institutions—vessels of enduring US imperial domination over Haiti—have contributed to the country’s current crisis can read China Miéville’s excellent analysis. The collaboration of global capitalism’s peak institutions is further discussed in this comprehensive study by Robert Knox.

The album’s most notable throughline is Mach’s emphasis on reflection and the knowledge of self, both individual and collective. He posits that such lucidity is a requisite foundation for the rejuvenation of Haiti, something Mach is clear will only be possible through radical means. #RICHAXXHAITIAN reflects a rap artist at the height of his powers, focused on vivid stylistic and political evocation. I highly recommend listening to it, as it must be 2024’s best rap album to date.

If you don’t mind, I would love to know what you think of these recommendations. Until next time!

Will have to add "Communist Hypothesis" to my reading list. Seems a point that is made too often, and I do yawn when people bring up the 'end of history francis f etc. etc.' , but an ideology is not made obsolescent when it loses political power. The class that put it into action still exists. Nor do classes often 'win' in their first moments of consciousness and political awakening. It often takes hundreds of years and a process of conflict, victory, and subsequent defeat, rinse and repeat for a class to even outline a working program for systematic political change. E.G. how long it took burghers in medieval/early modern Europe to go from "city and guild privileges matter!!!11111!!" to " I will murder the whole royal family" was quite a long and bloody process.