Reading, Watching, Listening / 10.09.2024

Practising with Guy Rundle, battling with Jane Schoenbrun and David Cronenberg and kicking it with Action Bronson and Party Supplies.

Another month, another discussion of the best and worst things I have been reading, watching, and listening to recently, presented for your enjoyment. Picking up where we left off, my book review of Slick by Australian investigative journalist and author Royce Kurmelovs is now available in Meanjin online. I mentioned that it was forthcoming last month. If you haven’t already, you can read it there—the book offers a thorough history of the Australian oil industry, its influence over federal politics and its accompanying contribution to climate armageddon.

I’m (once again) coming in a tad late since I have been and will still be travelling throughout Türkiye for a good minute. The good news is that despite the demands of roaming everywhere from Dersim to Marmaris, the temporary relief from everyday responsibilities, such as, among other things, full-time employment, has meant I’ve been able to think more. Yes, and this thinking has produced a great many ideas for pieces of writing that I hope to bring to you as soon as practicable. Without further ado, though, here is the sixth edition of Reading, Watching, Listening.

Reading: ‘Practice’, Guy Rundle

Guy Rundle has been writing and writing a lot for thirty-some years now. In the preface to Practice, a 2019 collection of his journalism, essays and criticism, he terms this time spent as a “writer-activist, [...] pro writer and hack” as “the rarest of opportunities”. Longtime correspondent-at-large for Crikey, Rundle travelled across America covering the 2008 Democratic Party primaries and the following Presidential election, continuing to write on developments as the Obama era gave way to the Trump age. He has traversed plenty of Australian escapades of similar nature, digging for insights from, for example, attendees at Liberal Party campaign launches who otherwise “went by and large uninterviewed, unasked, unencountered”.

This gig earned him a reputation as a ‘gonzo’ journalist, something he concedes is partially apt, though his approach is discernably more objective and overtly political than that stylistic Godfather, Hunter S. Thompson. Simultaneously, he was and is still writing for a raft of other outlets, from mainstream liberal mastheads to Arena—as far as I can tell, Australia’s longest-running magazine and journal of critical left-wing ideas. Convinced of Marxism at a young age, Rundle’s work as co-editor and frequent contributor to Arena is devoted to developing and applying the publication’s line of ‘post-Marxist’ thought. This translates to Arena aiming to reconstruct a radical left theory that more adequately addresses the enormous structural changes in capitalist society since the 70s. Modest, and something that oft-nobly intended but sclerotic socialist groupings hold a self-defeating hostility toward.

In the face of it all, Rundle readily acknowledges that he “was granted the sort of writing rhythm, with world travel thrown in, that writers read of with lip-licking envy”. Fucker. But in reading Practice, an anthology stitching together his day-to-day politico-journalism with more discursive pieces, I can only be glad that it was to Rundle that this golden opportunity, unlikely to emerge again in Australia as we know it today, fell. Using the term ‘journalism’—vulgarised in the extreme by the water-carrying, anti-knowledge profession it commonly denotes—to describe Rundle’s work feels misleading. Doing so, however, points precisely to what such a writing practice (there’s that title word) should be: a blend of thorough practical and philosophical inquiry with personal narrative and robust critique, always sensing its place in the movements of history.

As a young Australian writer (yeah, yeah, good on you, mate) who recently worked with Rundle for the first time, the apparent last copy of Practice—haphazardly displayed cover-first by the staff of the Avenue Bookstore in Albert Park—called out to me like a lost siren. Which is to say, lost to the all-encompassing sea of nothingness to which writing of this type, sponsored by commercial entities, has been condemned. Simply put, I sought an understanding of Rundle’s style and perspective and to trace how events, people and ideas, both before and during my adult life, were mediated by the country’s pioneering writer-of-type. Fortunately, Rundle leverages the extraordinary opportunities afforded to him as a means of memorialising. A concerted effort is made to bottle, if only across a few pages, everything from people of interest to political junctures and particular moments in the constant evolution of a city, be it Melbourne or London.

Take ‘Melbourne Interstitial’, one of the lengthier essays in the collection plucked from the 2015 book of the same title. At once a survey of the city as it was and a keenly observed account of its mutations, Rundle lovingly amplifies the heartbeat of a town that, despite being the place of my birth and where I have always lived to this point, evidently I never knew. Case in point: when I asked my parents about the red-vinyl cafes, those “two dozen or so low-lit, booth-crowded greasy spoons” once the most dependable inner-city tucker distributors on weekends, they blanked. No recollection. The shameless Americana appreciator in me almost jumped out of his skin.

Rundle’s description of these joints sounds like my personal heaven, from the “cardboard buckets” of chips then still hand-cut by wog owner-operators who have since sold up and negatively geared several investment properties, to sitting on a forty-cent black coffee “for hours at a time without anyone hassling you”. Today, maybe one restaurant in the entirety of inner Melbourne (Northern Soul, those delightful St Kilda-based UK expats) makes real fried potatoes—bonne chance if you’re looking for anything other than $12 McCain-brand freezer fries. When “cities forget themselves”, what’s lost isn’t just the formerly glorious, now hollowed-out buildings spotted by Rundle on his many walks, but its distinct cuisines, rhythms and lifemodes.

That sense of ways of life and attention paid to the temporality of existence—and his writing itself—is something more to enjoy in Rundle’s work. Interstitiality is one of Rundle’s principal concerns (if not his favourite word, appearing multiple times in multiple pieces), along with the decomposition of capitalism’s traditional classes, identity politics and the psycho-ideological machinations of anyone of note, be they Kurt Cobain or Malcolm Turnbull and Kevin Rudd. He never lets you forget that “one age is always overlapping the other”. In the corniest way possible, you can think of Practice as a meditation on the idea of practice itself, not merely as rote repetition like filing your daily reporting, but as deliberate, evermore close engagement with the world and its many revolutions. From the outset, it’s clear that Rundle won’t retread the well-worn paths of contemporary essayists: personal grievances, identity issues and unresolved traumas.

That’s not to say Rundle doesn’t feature in his writing; he certainly does for better, like when you benefit from his willingness to strike up a conversation with absolutely anyone, and for worse, like when he is a little too flippant in his self-aware maleness. Everything is seen and described through Rundle’s eye. But he accomplishes impressing a solid voice, his defined perspective, together with voraciously well-read philosophical musings, seamlessly shifting between the microcosm of his own experience and the macrocosm of broader social and political trends. Rundle is always there, but there’s a distance of intimist irony—genuine irony, not that meme shit—that permeates his work. That duality creates the tension and dynamism that propelled me to engage on multiple levels with every idea and devour the whole book in mere hours.

This facet of his writing finds its most poignant expression in his prolific coverage and analysis of Australian politics. I couldn’t think of another person who has more consistently and thoroughly subjected the direction of Australian political life to rigorous deciphering than Rundle. Shockingly, in the main, the role of “memory of the class” in this country has best been performed by an individual and not any socialist group. Rundle’s is substantive inquiry and critique at its best. Whether it is mining the void at the centre of Anzac Day that collapses every government attempt to make it an effective ideological locus of Australian society or shrewdly anatomising the changes in the nation’s social contract throughout my lifetime, I always find refreshment at the tip of Rundle’s knife.

Sure, he may be cataloguing how our “system of minimum friction in which the political caste can reproduce themselves smoothly” pushes cynicism and disillusionment to unbearable levels. It seems there isn’t a single figure in Australian politics for which Rundle has the slightest sympathy. But if that is the case, it is because, in the words of Jeremy George and William Holbrook, “if Australia’s provisionality, its lack of a deep historical sense, means it is a place where very little impedes the exploration and development of novel forms of evil, it also suggests to Rundle, in his most hopeful moments, the possibility for the trying-out of alternative, more fully human ways of life”.

Rundle’s writing has a prosaic quality that is hard to ignore; it’s like he’s plainspoken even when the language gets denser or more sectional, and that flow captivates well enough across the vast subject matter. Sometimes, this conversational approach leads to inscrutable sentences because your conversation partner can be a rambler—not always bad, except when their arguments are circuitous or lack a clear throughline, a more direct path through the thicket of ideas. But this singular, almost dogmatic approach is part of the book’s appeal. Insert cliche about being forced to slow down and wrestle with whether you think Rundle is entirely correct or if a particular suggestion has gone awry.

I wanted more film criticism, if for no reason but that the True Detective essay is one of the collection’s best. Even here, Rundle refuses to offer a simplistic explanation, connecting the philosophy of the show’s first season, still one of television’s best, to its embodied sense in an America that “can no longer comprehend itself”, which Rundle grew accustomed to on his travels. So, if you’re interested in Australia (hahaaa), experiencing what ‘journalism’ should be, and surrendering to the slippery slope of Rundle Thought, get your lazy arse to Practice. Or don’t. Instead, go outside for a long, long walk through your city, your daily dose of its very own interstitial—it won’t be there forever.

Watching: ‘I Saw The TV Glow’ (2024) dir. Jane Schoenbrun and ‘The Shrouds’ (2024) dir. David Cronenberg

Before jetting off to the land of börek and baklava, I was able to catch a few sessions at MIFF, though I missed so many more that I wanted to attend (goodbye, sweet Caught by the Tides, I’ve heard such pretty things about you). The best debut I saw was Raven Jackson’s All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt (2023), and I took enough notes that, if I can watch it again sometime, there could be a piece in there about her revival of time as a core cinematic device.

More to the point, knowing I had travel on the horizon, I made sure to see Jane Schoenbrun’s I Saw the TV Glow—a buzzy, star-making title produced by A24, making significant critical and social waves in the States—thinking I’d miss its general release. In light of the film’s rapturous reception, with “masterpiece” seemingly tossed into every second piece of writing about it like parsley into çoban salatası, I left surprisingly uneasy. I can’t offer a thorough review of the film, so I’ll use the space to explore my main problem with it and what the overexcited response tells us about the state of the arthouse today.

Suppose you’ve heard of I Saw the TV Glow. In that case, you no doubt heard of it in the context of its significance as “a profound vision of the trans experience”, as Richard Brody put it in The New Yorker. While Brody’s enthusiasm isn’t solely reserved for the idea that the film faithfully reproduces the ennui of transness (or not-so-transness), this is the dominant frame through which it is celebrated. People have gone as far as asserting that the film could “save lives”, alluding to the scourge of elevated suicide rates amongst trans people. If borne out, such an effect would be a categoric good. I note this only to give some idea of the intensity of identity-centric praise surrounding I Saw the TV Glow. Had Schoenbrun’s film managed to elevate the narrative beyond the flattening of transgenderism into a mere struggle to exist within a suffocating world—a riddle rendered through their eerily one-note perspective—I might feel inclined to lend my voice to the chorus.

The film presents itself as a clever piece of meta-commentary around the (very real) bleeding necessity for young queers to break from frustrated non-development and embrace their complete identity. Its main characters experience deep confusion in their identities, knowing something to be ‘off’ but incapable of articulating precisely what and, most importantly, breaking from their suburban stasis. I Saw the TV Glow explicitly aims to incite audience participation in this process, making it thuddingly apparent how the central metaphor of obsession with certain escapist media, a desperate appeal to that actual mass coping mechanism, is to be interpreted. Viewers are didactically instructed on the constellations of aborted transness through devices from fourth-wall-breaking narration to literal ‘counselling’ scrawled on screen during its dying frames (Jesus Christ).

If the film’s classroom form (staged around, ready for it? “Void High School”, abbreviated as VHS) wasn’t enough, Schoenbrun has spoken suspiciously candidly of all this in interviews. In one case, they spelled out to The Guardian that they “had been really fascinated with this idea of a cancelled TV show that ends in a terrible unresolved way. And I was obsessed with this idea of characters who were never really able to move on from this unresolved ending of a TV show. The metaphor at the centre of the film hinges on something being wrong, almost like an identity or a path being foreclosed in the moment”. Leaving aside the question of whether it is helpful for filmmakers to be hyper-confessional, there is no denying that Schoenbrun’s approach resonated widely with trans audiences. This is no surprise given that a protracted tousle with the spectre of one’s gender is so commonly a feature of trans life. The question is whether or not it achieves this in a dignifying manner and if it deserves extraordinary praise as a film.

That I Saw the TV Glow is but a big, tacky metaphor, one which feels avoidant of the fundamental conflicts it constantly gestures toward—expectations and abuse inside the nuclear family, the battle to be honest with oneself and others, the separation of self from synthetic media—hasn’t seemed to bother many. Respected figures have boasted that “one of the great accomplishments of Schoenbrun’s film is that it’s not subversive”, contrasting it unfavourably with Greta Gerwig’s Barbie (2023), which, to my mind, incorporates a far greater degree of nuance on matters of gender and the regime of images dominating identity and the actual. Indeed, Brody strongly feels that Schoenbrun’s cobbling together of devices, allusions, and obliqueness amounts to a nascent “distinctively trans [cinematic] aesthetic”.

Against this predominant position, I argue that the filtering of the struggle to actualise trans identity through a gimmicky simulated critique of pathologic media fandom is both aesthetically lazy and intellectually uninventive. To his credit, Brody at least attempts to articulate why Schoenbrun’s style is worthwhile, but that most long-form writing on the film almost entirely evades discussion of its very form is telling. Mostly, you see Schoenbrun’s unwillingness, or inability, to use a language other than bleating references to “Buffy, analog, nostalgia, suburbs” and David Lynch raised to the mark of self-reflexive genius. Such an “admission of unoriginality [...] elevated into a perverse aesthetic value” is, in reality, tiresome and regressive. We should question whether any insight can result from reducing the complexity of gender’s corporeal, psychological and social contradictions to a monotonous, handholding metaphor.

Additionally, the unambiguous command to transition and do it now is more insulting than liberating, regardless of any theoretical constructive impact. Schoenbrun’s refusal to explore queerness as anything but a half-formed, hurriedly buried thought neglects the vivid, autonomous experiences that might rupture and redefine the protagonist’s constrained world. It leaves the film’s zombification of him a flat, unearned flail at emotional venom. Desire, illusion, isolation, difference, and self—the content of the struggle I Saw the TV Glow ostensibly explores—have disappeared in Schoenbrun’s overpowering instinct to literalise, expose their rigid definitions, punish their protagonist, and demoralise their audience. This starkness erodes the singularity of the trans experience that the film is so ravenous to evoke, replacing complicated textures with “the obscenity of visibility”. By elevating their film to a warning to transition or face unmeaning, Schoenbrun’s film performs the very same violence of “oversimplification” that the “dominant political force” routinely prosecutes against trans people.

I Saw the TV Glow joins several recent entries into a new wave of pseudo-reflexive cinema—films like TÁR (2022) and Civil War (2024)—that, through an unbearable mixture of feigned ambiguity and political and moral hectoring in the extreme, engage their otherwise worthy subject matter only in the most surface-level of “relevancy”. That readily identifiable mimicry and mockery often receives widespread acclaim exposes that many who wish to protect arthouse cinema are tailing what they think should be a meaningful mediation of contemporary issues simply because they present themselves as such, without reflecting on whether this is true, and if so, how.

What is most alarming about this trend is not the use by directors of metafiction as a device but the poverty of thought behind it. It’s as if their films dare you to project your personal feelings—or even an elaborate metareading—onto them, to do the work of colouring them with the human granularity they lack glaringly in their own right. Rather than affirming audience agency as Schoenbrun intends, I Saw the TV Glow quacks like an abdication of artistic responsibility. The result is a paradoxically opaque and transparent film: opaque in its refusal to truly pursue its material and transparent in its motive, absence of meaning and pandering.

One film that I Saw the TV Glow is indebted to but embarrassed by is David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983). As though to cosmically upset Schoenbrun’s attempt to fashion trinkets of the past into a hotel toilet paper-thin visage of purpose grafted over the pointlessness their work shares with much of contemporary art, I followed Schoenbrun’s film with Cronenberg’s latest work, The Shrouds. If I Saw the TV Glow amplifies the intimate to the point of sheerness, then The Shrouds is the sparing hand that dims the harsh light to reveal a sinister tapestry lurking in the shadows.

Cronenberg continues his career-long exploration of the contemporary human condition but with a drier, more withdrawn artifice that is subversive and all the more meaningful for being so. Here, he sharpens his surgical scalpel, peeling back the layers of deceit, self-deceit and displacement we all engage in to reveal something both unmistakably human and disturbingly foreign. The film is a cold, clinical space where the human body is a site of constant transformation, where identity is not just fluid but downright liquid, capable of spilling over from or collapsing physical boundaries, evaporating entirely into the virtual.

Cronenberg’s late style is frequently misunderstood as a turn towards the esoteric, the obtuse, the nearly unwatchable. Indeed, quite a few audience members quit on my screening. Yet, with The Shrouds, the director again reasserts himself not as a simple provocateur but as a philosopher of form. The film is a genuinely inscrutable object that defies all attempts at categorisation as “body horror”, a “portrait of grief”, or “technoconspiracy thriller”; distinct from any other film yet totally coherent with Cronenberg’s project. Witnessing The Shrouds is like standing before a hall of mirrors reflecting not just the self but the infinite distortions that obscure true recognition. Therein lies the full force of cinema’s capacity to intervene, to arouse and provoke realisation and understanding.

Humanity is rarely so densely rendered, so palpably emanating from the screen, with Cronenberg baring so much that it appears alien and alienating. But I gently suggest that if you fail to recognise yourself in The Shrouds, this may be hesitancy to confront the deep undercurrents beneath your most private thoughts, impulses and habits. Cronenberg is antagonising without ever being cheap or obnoxious, a challenge we should take him up on. The film’s austerity and fragmentation—its refusal to pander or pull formal tricks to confect complexity—reflects respect for our ability to engage uncomfortably and a notable refusal to dictate terms, contrasting with Schoenbrun’s overwrought arrogance. Cronenberg mines more humour from the sublimely parodic and uncanny tone than ever. Vincent Cassel, who plays the lead, should receive his just deserts for a performance capable of playing conduit to immense intricacy.

I am avoiding plot specificity and examining themes because The Shrouds demands to be experienced without bestowed information. Similarly, you’d have to watch the film numerous times to construct an analysis worthy of its slippages, winking jabs and caustic critique. I left the cinema thinking about what a gift to the medium Cronenberg is and has always been. In a time when so much cinema is obsessed with explaining itself, screaming out its supposed meaning and providing neat resolution or instruction, The Shrouds is a welcome and vicious anomaly. Cronenberg trusts his audience to feel their way through its maze of images and ideas, which resemble the seductive shibboleths of its graveyard motif. It is a rare and beautiful thing in contemporary cinema: a work that refuses to be anything less than itself, unyielding in its scorn for those who cower away from fragility and uncertainty.

Listening: ‘Blue Chips’ and ‘Blue Chips 2’, Action Bronson & Party Supplies

Occasionally, a collaboration between an emcee and a producer clicks in a way that feels less like a commercial partnership and more like the genuine spark of shared artistic vision—a symbiosis of beats and bars that seemingly came into being irrevocably fused and at the same exact moment. This was precisely the case when Action Bronson teamed up with Brooklyn-based producer Party Supplies for their mixtapes, Blue Chips (2012) and Blue Chips 2 (2013). Then unsigned, Bronson joined Supplies at his home studio in Brooklyn “over YouTube sample digging, grub from local chicken joint Pies ‘n’ Thighs, and obligatory smoke sessions”, spawning a spontaneous musical experiment resulting in two of the most unconventional mixtapes in hip-hop history.

To understand the magic of the Blue Chips mixtapes, it helps to know a bit about Party Supplies. Eventually becoming a duo with Sean McMahon, at this point, from what I gather, Supplies was the solo moniker of Justin Nealis. With a knack for excavating unexpected sounds and creating loop-based, drum-heavy beats almost genreless in their ferocious channelling of countless influences, Supplies’ style is steeped in nostalgia. But this is not mere sentiment for past musical styles, including rock, pop, and soul—it’s the fashioning of a retrofuturist lo-fi signature from lost sounds that always contained the potential to become something wholly fresh.

Songs like ‘9-24-11’ open with chopped Dean Martin vocals, and when the thumping drums finally kick in, Supplies reveals the sample’s angelic choral backing. When he’s not cutting up heavenly vocals, he’s ripping absurdly groovy baselines into driving backdrops for Bronson’s culinary-infused street tales (“Steamed red snapper, Vietnamese / Catch a case, get a Jewish lawyer, beat it wit’ cheese”). The charm lies in the unexpected; you never quite know what you’ll hear next, not only in between tracks but within the songs themselves.

By the time Blue Chips 2 dropped in 2013, there was already a noticeable stylistic evolution. The rawness is still there but is more refined and further layered. Samples aren’t slapped together but carefully plucked to evoke a particular mood or catch the listener off guard just the right way. On tracks like ‘Pepe Lopez’, Party Supplies intersperses a bouncy, Latin jazz sample with boom-bap, creating an infectious, off-kilter rhythm over which Bronson declares he wears a bib “all muthafucking day”.

Unquestionably, the style reaches its apex on ‘Contemporary Man’, a thrilling four-minute medley across at least seven samples involving not one but five beat switches, each fixed on a popular single of the 1980s. Hear Bronson brag that he’s “Just a white man excelling in a Black sport, like I’m Pistol Pete” to Peter Gabriel and indulge in “Oyster bowls chilling in the cloisters” over Phil Collins. I see no conclusion other than it must be one of the most inspired rap songs of the genre’s young lifespan.

And then there’s Action himself, whose lyricism is as unique and colourful as the production it finds itself enmeshed in. Bronson is a classically trained former chef with a palate for language and imagery that’s slapstick and classy at once—dropping food rhymes and sports references into tales of debauchery, high-stakes street narratives, and fantastical scenarios. You will not hear anyone else string together more varied cross-cultural elements, delivering them as effortlessly and hungrily as Bronson does on tracks like ‘Double Breasted’.

A while back, I wrote about the contradictory cacophony of Bronson’s lyricism as a means with which to engage directly with one of the central tensions within the hip-hop genre. The argument in abridged form is that while Bronson articulates a value system that privileges the pleasures of an adventurous life over crude materialism, staunch as to the inherent worth of niche personalities, it frequently commits that original rap sin, misogyny. Nowhere is that more apparent than on the first Blue Chips mixtape, and it’s worth thinking seriously about the clash between Bronson’s liberated imagination and the real oppression faced by women and ‘outsiders’ today.

So why bring up the Blue Chips series now, more than a decade after their release and at a time when Bronson has seemingly left his best rapping behind? There is, of course, the aforementioned alchemy of collaboration, an impossibly captivating coalescence of the styles of rapper and producer alike. When Bronson later released Blue Chips 7000 with a range of producers as a studio album, it was clear that the original was irreplicable, lost in translation. Sure, 7000 is good in its own right—solid, well-produced, and with flashes of brilliance—but the entire sound of the project is unrecognisable from that which it draws down its name. It’s proof that this style of music, born of ephemeral energy, is impossible to domesticate to commercial demands, which impose the intellectual property regime and marketability concerns on the act of creation.

On Blue Chips, you’re never more than a few bars away from hearing Party Supplies shout something in the background (“yeah!”) or a beat ending abruptly because they’ve moved on to something else, something better. It’s that rough-around-the-edges quality that makes these tapes so compelling. You can hear the urgency and eclecticism in every track, cutting against the overproduced yet stripped-back aesthetic of hip-hop today. It’s as if you’re right there with them, in that Brooklyn apartment, as they dig through vinyl crates or roam the digital highways of YouTube for a sample to appropriate. In the way that Guy Rundle once wrote about 9Gem being the best way to experience TV—unplanned, erratic, kaleidoscopic and dichotomous—the Blue Chips tapes make the similar joy of rap music a spin away.

It’s also because I’m just in the damn mood, travelling around a country stuffed to the brim with its own incomprehensible strangeness, cultural riches and culinary ecstasy. These tapes are the perfect soundtracks for moments when you want to break away from the ordinary, when you’re on the road or on vacation, seeking the succulent delights of the good life. The Blue Chips projects rise to the highest aspiration of the mixtape—not merely a collection of sameish songs, as Spotify playlists are; they prompt, not simply represent, a state of mind. They remind you of what it’s like to be truly free, to create without constraints, and to live in the moment. They’re a testament to the power of collaboration and the beauty of dissonance. By modelling what makes hip-hop exciting in the first place—the breaking of rules, the fusion of diverse influences, the creation of something distinct out of disparate elements—they provide a blueprint for innovations yet to come.

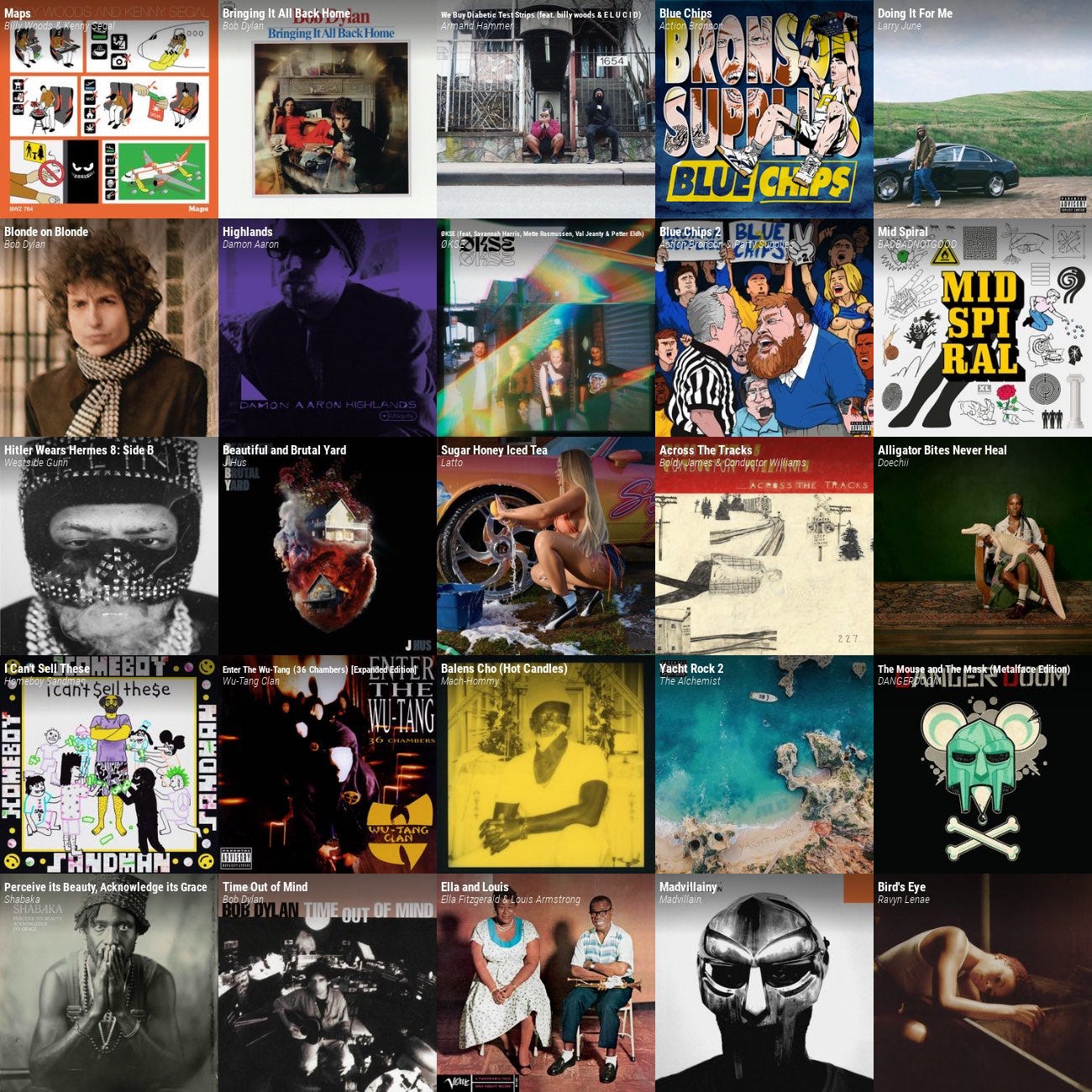

Thanks for sticking with me for such a beefy edition. I wanted to bring you something valuable, given I’m a touch late. To sign off, here’s what I listened to the most in August, 2024:

Love it Revan! Highly agreed on the Bronson mixtapes as you know, classic series! Perfect listening for your travels

Congratulations on the Meanjin article, levendi! I enjoyed reading it.