Hip-hop is dying? To save it, 'Return to the 36 Chambers'

Ol' Dirty Bastard's uninhibited 1995 debut is rich with lessons for today.

Travis Scott’s highly anticipated fourth studio album ‘UTOPIA’ opens with “Hyaena”, a song introduced with a sample of the British band Gentle Giant:

“The situation we are in at this time

Neither a good one, nor is it so unblessed

It can change, it can stay the same

I can say, I can make my claim

Hail, hail, hail.”

It is the album’s sole moment of lucidity. Scott incisively diagnoses two facts for just 26 seconds of the one-hour and 14-minute record. First, Scott has been crowned one of the mainstream kings of the genre, having nine Grammy nominations, two number-one albums and millions of record sales to his name. Second, the music industry (like other creative industries in the current crisis of capitalism) is experiencing a period of uncertainty, which contains both the possibility of rebirth and continued disruption.

This diagnosis is particularly interesting when one considers that despite a five-year wait and Scott’s massive profile, ‘UTOPIA’ failed to replicate the number one Billboard debut achieved by his preceding two albums. What does it say when a self-proclaimed king of his country’s most popular music genre can no longer take the throne?

Some have connected this to hip-hop’s overall failure to dominate the charts in 2023, as it has done in recent years. There is a growing perception that hip-hop is at a crossroads, with many lamenting its commercial homogenisation and apparent creative stagnation. Curiously, this comes as hip-hop is celebrating its 50th birthday.

Even the most thoughtful reflections on the yet youthful genre’s milestone simultaneously mourn its premature death. It’s easy to see why when taking stock of the genre’s peak. Kanye West, arguably the artist most responsible for hip-hop hegemonising the mainstream, was lost to an explicitly anti-Black Nazism.

Kendrick Lamar’s albums are increasingly, and I think, intentionally tiresome, betraying a hatred of his public profile and listeners. And Drake, who, like West, repeatedly reshaped the hip-hop landscape for better and worse, isn’t rapping much or very well anymore. So, Travis Scott is hardly alone as a hip-hop superstar struggling to define themselves or recreate the once-epochal nature of their records.

As a tragic for the genre, I’ve been thinking about this question and discussing it with friends. Within this context, I revisited one of the records that most inspired my love for hip-hop as a teen: Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s 1995 album, ‘Return to the 36 Chambers’. I immediately realised this rediscovery may hold the key to revitalising hip-hop's spirit.

Russell Tyrone “Ason” Jones, better known by his oft-abbreviated stage name, Ol’ Dirty Bastard (ODB), was a Brooklyn-born founding member of the Wu-Tang Clan rap group. ‘Return to the 36 Chambers’ was released only two years after the Clan rose to prominence with their debut album, ‘Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)’. That group debut now enjoys iconic stature for its supremely skilled albeit rugged lyricism, menacingly gritty production and conceptual ‘Soul-Fu’ pastiche.

As its title suggests, ODB’s first solo record marked a return to this sound, pioneered by the Clan’s in-house producer, RZA. While ‘Return’ inhabits the same world as ‘Enter’, RZA’s production creates the distinct sense that ODB’s eclecticism was integral to constructing that world. Method Man states as much on track five of ‘Enter’, remarking that:

“Cause there ain't no father to his style

That's why he the Ol' Dirty Bastard.”

This primordial creation myth is realised on ‘Return’ via a once-in-history combination of RZA’s indecorous production and ODB’s ravenous vocal style, where the very concept of flow is at once mastered and usurped. ‘UTOPIA’ opens with insight that immediately melts down into deflection. The intro skit to ‘Return’ is similarly blunt in its thesis, with ODB introducing himself to a live audience by anointing himself James Brown’s successor and launching into a typically misogynistic Brownesque creed about contracting gonorrhoea twice.

Suppose it wasn’t already apparent that you’re in for a wildly vile, sharply contradictory ride. In that case, ODB injects a sudden tenderness, drawing raucous applause from the audience by singing about the feeling of getting head from your crush for the first time. Unlike Scott’s album, though, ODB follows through on the much loftier task he sets himself. This task is a profoundly reflexive, credibly boastful, yet sincerely self-abasing artistic singularity with no precedent in any genre–let alone hip-hop.

At the heart of the album's significance is its production, primarily helmed by RZA, with a couple of exceptions co-produced by ODB himself. One can tell as much because no album released since has sounded like this. Where modern acts like JPEGMAFIA meticulously manufacture merely the signifiers of impurity while lacking genuine pathos, 'Return to the 36 Chambers' revels in its unrefined comeliness. As ODB puts it:

“See when you stimulate your own mind for one common cause

You see who's the real motherfuckers”

Unlike the strained extravagance of Scott's 'UTOPIA', where transitions are needlessly imposed to feign dynamism, ODB's album lets the music breathe. Extended beat loops with thumping boom bap drums and syncopated samples create an unbroken spell, from the savagely arranged piano on “Shimmy Shimmy Ya” to the unfuckwithable bass on “Baby C’mon”. Listeners are gradually drawn into a hypnotic trance from one track to another, bopping our heads anxiously awaiting the next ODB verse to exhilarate us.

Take “Brooklyn Zoo”, which has a serious case for being the very best of all the illustrious Wu-Tang-associated songs. ODB co-produced the scintillating, distorted piano-based instrumental with True Master. Honestly, I wonder if any rapper has exhibited such consummate control over their craft as Dirty here. His verses are a whirlwind of vocal gymnastics, where his flow careens between staccato and fluid, rapped and sung–it’s nonsensical brilliance.

“My hip-hop drops on your head like ra-a-aaain

And when it rains it pours, 'cause my rhymes hardcore

That's why I give you more of the raw

Talent that I got will rizzock the spot

MCs I'll be burning, burning hot.”

This earned braggadocio delivered in electrifying fashion follows a reference to a notorious psych ward–the G Building–in ODB’s native Brooklyn, which eventually closed following revelations of obscene abuses against patients. At his most triumphant, ODB remains rooted in a rare honesty toward traumatic experience.

Indeed, Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s explosive persona was not confined to his art; his struggles with poverty, addiction, violence and the legal issues that followed became integral to his legacy. To the strange cacophony of sounds that seem to unwind and reload like a mesmerising spring on “Raw Hide”, ODB explains:

“Who the fuck wanna be an emcee

If you can't get paid to be a fuckin' emcee?”

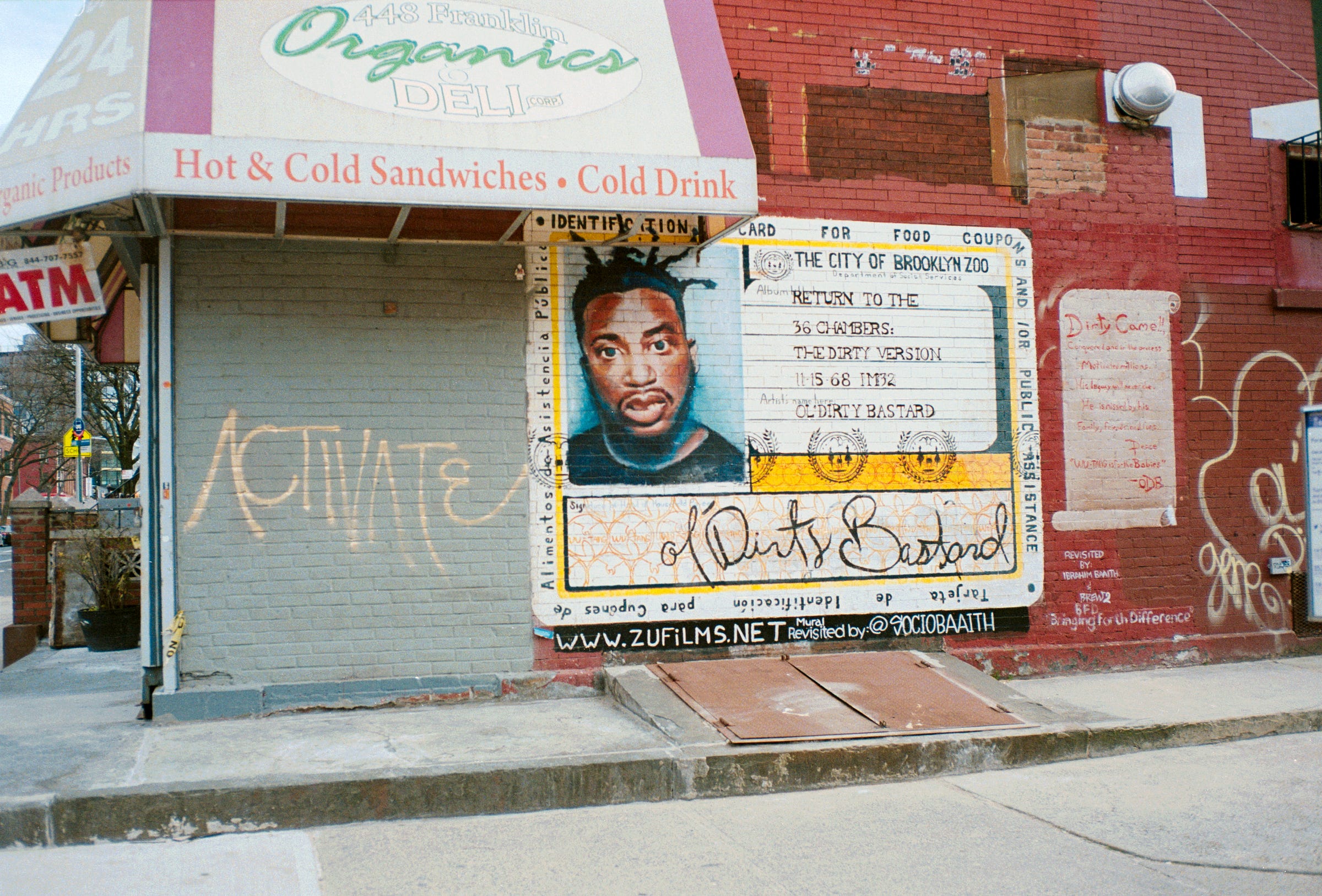

RZA once recalled that the inspiration behind these lyrics was that despite the Wu having record deals, most of their budgets went into making the records with expenses like paying for samples, lawyers and studio time. “This left a artist having to hit the street for shows in order to cake up.” ODB echoes the album artwork featuring his food stamp identification card:

“I came out my momma pussy, I'm on welfare

Twenty-six years old–still on welfare

So I gotta get paid fully

Whether it's truthfully or untruthfully.”

ODB’s uncanny rapping ability and collaborative luminosity amongst the Clan eventually enabled him to abate these material pressures substantially. Although Dirty was insistent about his hustle, he wasn’t selfish. Once he had money, he became known for handing it out, including to children in the street.

Despite its unconventional content and form, ‘Return to the 36 Chambers’ achieved critical acclaim and commercial success, earning a Grammy nomination in 1996. While it failed to win ‘Best Rap Album’, it is impossible to imagine an equally subversive record, much less a hip-hop debut, even receiving a nomination today.

Consider that, as Sheldon Pearce once noted, ODB weathered intensely racist scrutiny for his apparent disreputable character, “a depiction of a kind of blackness that was obscene: ignorant, dependant, deviant, unkempt, unruly, and, worst of all, uncontrollable”. This made his momentary stardom remarkable. One listen to ‘Return’ proves that Dirty possessed an acute understanding of the public characterisation of his persona, which he carefully reconfigures into a revolutionary anti-aesthetic.

It is essential to admire ODB’s transcendence of his life’s trappings in his artwork without viewing them solely as artistic fuel. No, as a poor, mentally ill Black man suffering from drug addiction, ODB absorbed profound harms ranging from being shot multiple times to becoming wary of doctors and incarcerated for cocaine possession. At one point, he escaped from a court-mandated drug treatment facility. During his month on the run, it is striking that he couldn’t resist playing a concert or recording music with RZA. The great tragedy of this story is that ODB’s defiance and material success weren’t enough to prevent his early death in 2004 due to a drug overdose.

Brian Michael Murphy eloquently captured the devastation such unnecessary deaths of despair represent within hip-hop, where “the tragic circumstances of [its] urban crucibles, and their attendant foreshortened life chances, are inseparable from its energy, aren’t they? They are. But I still feel mournful, for that time, for those people, for the things that were possible back then, and for what we as a society are losing now, in our inability or unwillingness to do better than we have done. What stars are now collapsing in on themselves before they’ve even had the chance to rise?”

There is no reconciling this burning truth just by listening to classic, transformative records like Ol' Dirty Bastard's ‘Return to the 36 Chambers’. But there is some solace in tracing his influence far beyond his era. Many have remarked that Dirty’s unapologetic individuality paved the way for artists like Young Thug and Danny Brown, who undoubtedly have adopted elements of his persona and vocal delivery. But beyond these observations, the most fascinating of ODB’s echoes in the present is E L U C I D, the Jamaica, Queens rapper who forms one half of Armand Hammer.

In E L U C I D’s music, you find few, if any, superficial similarities to that of ODB. But the high level aesthetic differences between their styles belie a deeper connection. The ODB particles in E L U C I D don’t relate to the specific vocal sounds he conjures but to their shared, seemingly endless vocal elasticity. After about four songs of ‘Return to the 36 Chambers’, you will have lost count of the variety of flows or specific “singing” techniques deployed by Dirty. The experience of E L U C I D’s 2022 album ‘I Told Bessie’ is almost equally diversified, disarming the listener with a delicate balance between total smooth and Iggy Pop gruff. Listen a little closer, and the lyrical synthesis reveals itself in their mutually autocritical and existential songwriting:

“There’d be no blues if I was blameless.”

This subterranean interrelation between Dirty and an artist whose debut came 21 years after ‘Return to the 36 Chambers’ suggests hip-hop isn’t dying. This isn’t to minimise the structural obstacles to the development of great hip-hop that exist today; the dominance of streaming platforms and digital marketing have supplanted the centrality of organic art and the live experiences that built the genre. ODB himself built his imperishable rapping skill through tireless street-based live performances:

“Native, he used to beatbox, thousands would listen

Yo, that's before, the Wu got on.”

Dirty internalised the need to inspirit crowds with his talent as his core artistic responsibility and a measuring stick by which his ability should be judged:

“I get riggy diggy raw when it's time to get

On the dance floor shotgun kill the shit

Blaow, then you won't step to me

Thinking is he really raw as he said he'd be

If I wasn't really raw, standing here on the floor

You'd be like, "Booooo! He ain't hardcore!"”

Now, success and respect doesn’t correlate with one’s commitment to the actual craft of rap, but largely with who is the beneficiary of the slickest management of their confected image. It could be something of a metaphor that Travis Scott achieved notoriety for his live performance style, aptly termed “raging”, only to refrain from commenting on this again following the infamous Astroworld disaster. Unable to take pride in the collective experience his music once created, Scott is reduced to gasbagging about nothing.

In the wake of the hollow triumphalism that currently dominates, the hip-hop renascence will require a renewed embrace of the long-standing vulnerability that once prominently flowed through its veins. It is the work of artists like E L U C I D, with its dual social and introspective honesty in the image of ODB, that forms the glue that can mend the fractured identity of hip-hop. Let a thousand flowers bloom, and a thousand schools of thought contend. In this musical garden, it’s the artists who dare to expose their roots who have the potential to reshape the future of hip-hop, offering a path back to its soulful, unvarnished essence.

Thanks again to Reece Hooker for contributing his wise editing.